Cherokee language

| Cherokee

(Tsalagi Gawonihisdi) |

||

|---|---|---|

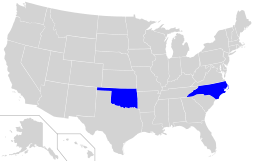

| Spoken in | ||

| Region | Oklahoma and the Qualla Boundary, North Carolina | |

| Total speakers | 12,000 to 22,000 [1] | |

| Language family | Iroquoian

|

|

| Writing system | Cherokee syllabary, Latin alphabet | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1 | None | |

| ISO 639-2 | chr | |

| ISO 639-3 | chr | |

| Linguasphere | ||

|

||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Cherokee (ᏣᎳᎩ, Tsalagi) is an Iroquoian language spoken by the Cherokee people which uses a unique syllabary writing system. It is the only Southern Iroquoian language that remains spoken.[2] Cherokee is a polysynthetic language.

Contents |

North American etymology

The North American origins and eventual English language form of "Cherokee" were researched by James Mooney in the nineteenth century. In his Myths of the Cherokee (1888) he reports:

- It first appears as Chalaque in the Portugese narrative of De Soto's expedition, published originally in 1557, while we find Cheraqui in a French document of 1699, and Cherokee as an English form as early, at least, as 1708. The name thus has an authentic [English-language] history of 360 years.[3]

Modern Dialects

Cherokee has three major dialects. The Lower dialect became extinct around 1900. The Middle or Kituhwa dialect is spoken by the Eastern band on the Qualla Boundary. The Overhill or Western dialect is spoken in Oklahoma.[4] The Overhill dialect has an estimated 9000 speakers.[5] The Lower dialect spoken by the inhabitants of the Lower Towns in the vicinity of the South Carolina-Georgia border had r as the liquid consonant in its inventory, while both the contemporary Kituhwa or Ani-kituwah dialect spoken in North Carolina and the Overhill dialects contain l. As such, the word "Cherokee" when spoken in the language is expressed as Tsalagi (pronounced Jah-la-gee, Cha-la-gee, or Cha-la-g or TSA la gi by giduwa dialect speakers) by native speakers.

Phonology

Cherokee only has one labial consonant, m–which is relatively new to the language–unless one counts the Cherokee w a labial instead of a velar. The language also lacks p and b. In the case of p, qu is often substituted (as in the name of Cherokee Wikipedia, Wi-gi-que-di-ya).

Consonants

The consonant inventory for North Carolina Cherokee is given in the table below. The consonants of all Iroquoian languages pattern so that they may be grouped as (oral) obstruents, sibilants, laryngeals, and resonants (Lounsbury 1978:337). Obstruents are non-distinctively aspirated when they precede h. There is some variation in how orthographies represent these allophones. The orthography used in the table represents the aspirated allophones as th, kh, and tsh. Another common orthography represents the unaspirated allophones as d, g, and dz and the aspirated allophones as t, k, and ts (Scancarelli 2005:359–62).

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | t | k | ʔ | ||

| Affricate | ts | ||||

| Fricative | s | h | |||

| Nasal | m | n | |||

| Approximant | l | j (y) | ɰ (w) |

Vowels

There are six short vowels and six long vowels in the Cherokee inventory. As with all Iroquoian languages, this includes a nasalized vowel (Lounsbury 1978:337). In the case of Cherokee, the nasalized vowel is a schwa, which most orthographies represent as v and is pronounced [ɜ] as "u" in "but"; since it is nasal, it sounds rather like French un. Vowels can be short or long.[6]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː | u uː | |

| Mid | e eː | ə̃ ə̃ː | o oː |

| Open | a aː |

Diphthongs

Cherokee has only one diphthong native to the language:

- ai /ai/

Another exception to the phonology above is the modern Oklahoma use of the loanword "automobile," with the /ɔ/ sound and /b/ sound of English.

Tone

Cherokee has a robust tonal system in which tones may be combined in various ways, following subtle and complex tonal rules that vary from community to community. While the tonal system is undergoing a gradual simplification in many areas (no doubt, as part of Cherokee often falling victim to second-language status), the tonal system remains extremely important in meaning and is still held strongly by many, especially older speakers. It should be noted that the syllabary does not normally display tone, and that real meaning discrepancies are rare within the native-language Cherokee-speaking community. The same goes for transliterated Cherokee ("osiyo", "dohitsu", etc.), which is rarely written with any tone markers, except in dictionaries. Native speakers can tell the difference between tone-distinguished words by context.

Grammar

Cherokee, like many Native American languages, is polysynthetic, meaning that many morphemes may be linked together to form a single word, which may be of great length. Cherokee verbs, the most important word type, must contain as a minimum a pronominal prefix, a verb root, an aspect suffix, and a modal suffix.[7] For example, the verb form ge:ga, "I am going," has each of these elements:

Verb form ge:ga g- e: -g -a PRONOMINAL PREFIX VERB ROOT "to go" ASPECT SUFFIX MODAL SUFFIX

The pronominal prefix is g-, which indicates first person singular. The verb root is -e, "to go." The aspect suffix that this verb employs for the present-tense stem is -g-. The present-tense modal suffix for regular verbs in Cherokee is -a

The following is a conjugation in the present tense of the verb to go.[8] Please note that there is no distinction between dual and plural in the 3rd person.

Full conjugation of Root Verb-e- going Singular Dual incl. Dual excl. Plural excl. Plural incl. 1st gega - I'm going inega - We're going (you + I) osdega - We two are going (not you) otsega - We're all going (3+, not you) idega we're all going (3+, including you) 2nd hega - you're going 'sdega - you two are going itsega - you are all going 3rd ega - (s)he/it's going anega They are going

The translation uses the present progressive ("at this time I am going"). Cherokee differentiates between progressive ("I am going") and habitual ("I go") more than English does.

The forms gegoi, hegoi, egoi represent "I often/usually go", "you often/usually go", and "he often/usually goes", respectively.[8]

Verbs can also have prepronominal prefixes, reflexive prefixes, and derivative suffixes. Given all possible combinations of affixes, each regular verb can have 21,262 inflected forms.

Cherokee does not make gender distinctions. For example, gawoniha can mean either "she is speaking" or "he is speaking."[9]

Shape Classifiers in Verbs

Some Cherokee verbs require special classifiers which denote a physical property of the direct object. Only around twenty common verbs require one of these classifiers (such as the equivalents of "pick up", "put down", "remove", "wash", "hide", "eat", "drag", "have", "hold", "put in water", "put in fire", "hang up", "be placed", "pull along"). The classifiers can be grouped into five categories:

1. Live

2. Flexible (most common)

3. Long (narrow, not flexible)

4. Indefinite (solid, heavy relative to size)

5. Liquid (or container of)

Example:

| Classifier Type | Cherokee | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Live | hikasi | Hand him (something living) |

| Flexible | hinvsi | Hand him (something like clothes, rope) |

| Long, Indefinite, Liquid | hidisi | Hand him (something like a broom, pencil) |

| Indefinite | hivsi | Hand him (something like food, book) |

| Liquid | hinevsi | Hand him (something like water) |

Word Order

Simple declarative sentences usually have a subject-verb-object word order. Negative sentences have a different word order. Adjectives come before nouns, as in English. Demonstratives, such as nasgi ("that") or hia ("this"), come at the beginning of noun phrases. Relative clauses follow noun phrases.[10] Adverbs precede the verbs that they are modifying. For example, "she's speaking loudly" is asdaya gawoniha (literally, "loud she's-speaking").[10]

A Cherokee sentence may not have a verb as when two noun phrases form a sentence. In such a case, word order is flexible. For example, na asgaya agidoda ("that man is my father"). A noun phrase might be followed by an adjective, such as in agidoga utana ("my father is big"). [11]

Writing system

Cherokee is written in an 85-character syllabary invented by Sequoyah (also known as Guest or George Gist). Some symbols resemble Latin alphabet letters, but with completely different sound values; Sequoyah had seen English, Hebrew, and Greek writing but did not know how to read them.[12]

Two other writing systems beside the syllabary are a simple Latin alphabet transliteration of the language or a linguistic system with diacritical marks.[13]

Books in Cherokee

- Awi Uniyvsdi Kanohelvdi ᎠᏫ ᎤᏂᏴᏍᏗ ᎧᏃᎮᎸᏗ: The Park Hill Tales. (2006) Sixkiller, Dennis, ed.

- Baptism: The Mode

- Cherokee Almanac (1860)

- "Christmas in those Days"

- Cherokee Driver's Manuel

- Cherokee Elementary Arithmetic (1870)

- "The Cherokee People Today"

- Cherokee Psalms: A Collection of Hymns in the Cherokee Language (1991). Sharpe, J. Ed., ed. and Daniel Scott, trans. ISBN 978-0935741162

- Cherokee Spelling Book (1924). J. D. Wofford

- Cherokee Stories. (1966) Spade & Walker

- Cherokee Vision of Elohi (1981 and 1997). Meredith, Howard, Virginia Sobral, and Wesley Proctor. ISBN 978-0966016406

- The Four Gospels and Selected Psalms in Cherokee: A Companion to the Syllabary New Testament (2004). Holmes, Ruth Bradley. ISBN 978-0806136288.

- Na Tsoi Yona Ꮎ ᏦᎢ ᏲᎾ: The Three Bears. (2007) Keeter, Ray D. and Wynema Smith. ISBN 0-9777339-0-4.

- Na Usdi Gigage Agisi Tsitaga Ꮎ ᎤᏍᏗ ᎩᎦᎨ ᎠᎩᏏ: The Little Red Hen. (2007) Smith, Wynema and Ray D. Keeter. ISBN 978-0-9777339-1-0.

Word Creation

Due to the polysynthetic nature of the Cherokee language, new and descriptive words in Cherokee are easily constructed to reflect or express modern concepts. Some good examples are ditiyohihi (Cherokee:ᏗᏘᏲᎯᎯ) which means "he argues repeatedly and on purpose with a purpose." This is the Cherokee word for "attorney." Another example is didaniyisgi (Cherokee:ᏗᏓᏂᏱᏍᎩ) which means "the final catcher" or "he catches them finally and conclusively." This is the Cherokee word for "policeman."[14]

Many words, however, have been adopted from the English language – for example, gasoline, which in Cherokee is gasoline (Cherokee:ᎦᏐᎵᏁ). Many other words were adopted from the languages of tribes who settled in Oklahoma in the early 1900s. One interesting and humorous example is the name of Nowata, Oklahoma. The word "nowata" is a Delaware word for "welcome" (more precisely the Delaware word is "nuwita" which can mean "welcome" or "friend" in the Delaware language). The white settlers of the area used the name "nowata" for the township, and local Cherokees, being unaware the word had its origins in the Delaware language, called the town Amadikanigvnagvna (Cherokee:ᎠᎹᏗᎧᏂᎬᎾᎬᎾ) which means "the water is all gone gone from here" – i.e. "no water."[15]

Other examples of adopted words are kawi (Cherokee:ᎧᏫ) for coffee and watsi (Cherokee:ᏩᏥ) for watch (which led to utana watsi (Cherokee:ᎤᏔᎾ ᏩᏥ) or "big watch" for clock).[15]

Meaning extension can be illustrated by the words for "warm" and "cold". They also mean "south" and "north" by an obvious extension. Around the time of the American Civil War, they were further extended to US party labels, Democratic and Republican, respectively.

Language drift

There are two main dialects of Cherokee spoken by modern speakers. The Giduwa dialect (Eastern Band) and the Otali Dialect (also called the Overhill dialect) spoken in Oklahoma. The Otali dialect has drifted significantly from Sequoyah's syllabary in the past 150 years, and many contracted and borrowed words have been adopted into the language. These noun and verb roots in Cherokee, however, can still be mapped to Sequoyah's syllabary. In modern times, there are more than 85 syllables in use by modern Cherokee speakers. Modern Cherokee speakers who speak Otali employ 122 distinct syllables in Oklahoma.

| Otali Syllable | Sequoyah Syllabary Index | Sequoyah Syllabary Chart | Sequoyah Syllable |

| nah | 32 | Ꮐ | nah |

| hna | 31 | Ꮏ | hna |

| qua | 38 | Ꮖ | qua |

| que | 39 | Ꮗ | que |

| qui | 40 | Ꮘ | qui |

| quo | 41 | Ꮙ | quo |

| quu | 42 | Ꮚ | quu |

| quv | 43 | Ꮛ | quv |

| dla | 60 | Ꮬ | dla |

| tla | 61 | Ꮭ | tla |

| tle | 62 | Ꮮ | tle |

| tli | 63 | Ꮯ | tli |

| tlo | 64 | Ꮰ | tlo |

| tlu | 65 | Ꮱ | tlu |

| tlv | 66 | Ꮲ | tlv |

| tsa | 67 | Ꮳ | tsa |

| tse | 68 | Ꮴ | tse |

| tsi | 69 | Ꮵ | tsi |

| tso | 70 | Ꮶ | tso |

| tsu | 71 | Ꮷ | tsu |

| tsv | 72 | Ꮸ | tsv |

| hah | 79 | Ꮿ | ya |

| gwu | 11 | Ꭻ | gu |

| gwi | 40 | Ꮘ | qui |

| hla | 61 | Ꮭ | tla |

| hwa | 73 | Ꮹ | wa |

| gwa | 38 | Ꮖ | qua |

| hlv | 66 | Ꮲ | tlv |

| guh | 11 | Ꭻ | gu |

| gwe | 39 | Ꮗ | que |

| wah | 73 | Ꮹ | wa |

| hnv | 37 | Ꮕ | nv |

| teh | 54 | Ꮦ | te |

| qwa | 06 | Ꭶ | ga |

| yah | 79 | Ꮿ | ya |

| na | 30 | Ꮎ | na |

| ne | 33 | Ꮑ | ne |

| ni | 34 | Ꮒ | ni |

| no | 35 | Ꮓ | no |

| nu | 36 | Ꮔ | nu |

| nv | 37 | Ꮕ | nv |

| ga | 06 | Ꭶ | ga |

| ka | 07 | Ꭷ | ka |

| ge | 08 | Ꭸ | ge |

| gi | 09 | Ꭹ | gi |

| go | 10 | Ꭺ | go |

| gu | 11 | Ꭻ | gu |

| gv | 12 | Ꭼ | gv |

| ha | 13 | Ꭽ | ha |

| he | 14 | Ꭾ | he |

| hi | 15 | Ꭿ | hi |

| ho | 16 | Ꮀ | ho |

| hu | 17 | Ꮁ | hu |

| hv | 18 | Ꮂ | hv |

| ma | 25 | Ꮉ | ma |

| me | 26 | Ꮊ | me |

| mi | 27 | Ꮋ | mi |

| mo | 28 | Ꮌ | mo |

| mu | 29 | Ꮍ | mu |

| da | 51 | Ꮣ | da |

| ta | 52 | Ꮤ | ta |

| de | 53 | Ꮥ | de |

| te | 54 | Ꮦ | te |

| di | 55 | Ꮧ | di |

| ti | 56 | Ꮨ | ti |

| do | 57 | Ꮩ | do |

| du | 58 | Ꮪ | du |

| dv | 59 | Ꮫ | dv |

| la | 19 | Ꮃ | la |

| le | 20 | Ꮄ | le |

| li | 21 | Ꮅ | li |

| lo | 22 | Ꮆ | lo |

| lu | 23 | Ꮇ | lu |

| lv | 24 | Ꮈ | lv |

| sa | 44 | Ꮜ | sa |

| se | 46 | Ꮞ | se |

| si | 47 | Ꮟ | si |

| so | 48 | Ꮠ | so |

| su | 49 | Ꮡ | su |

| sv | 50 | Ꮢ | sv |

| wa | 73 | Ꮹ | wa |

| we | 74 | Ꮺ | we |

| wi | 75 | Ꮻ | wi |

| wo | 76 | Ꮼ | wo |

| wu | 77 | Ꮽ | wu |

| wv | 78 | Ꮾ | wv |

| ya | 79 | Ꮿ | ya |

| ye | 80 | Ᏸ | ye |

| yi | 81 | Ᏹ | yi |

| yo | 82 | Ᏺ | yo |

| yu | 83 | Ᏻ | yu |

| yv | 84 | Ᏼ | yv |

| to | 57 | Ꮩ | do |

| tu | 58 | Ꮪ | du |

| ko | 10 | Ꭺ | go |

| tv | 59 | Ꮫ | dv |

| qa | 73 | Ꮹ | wa |

| ke | 07 | Ꭷ | ka |

| kv | 12 | Ꭼ | gv |

| ah | 00 | Ꭰ | a |

| qo | 10 | Ꭺ | go |

| oh | 03 | Ꭳ | o |

| ju | 71 | Ꮷ | tsu |

| ji | 69 | Ꮵ | tsi |

| ja | 67 | Ꮳ | tsa |

| je | 68 | Ꮴ | tse |

| jo | 70 | Ꮶ | tso |

| jv | 72 | Ꮸ | tsv |

| a | 00 | Ꭰ | a |

| e | 01 | Ꭱ | e |

| i | 02 | Ꭲ | i |

| o | 03 | Ꭳ | o |

| u | 04 | Ꭴ | u |

| v | 05 | Ꭵ | v |

| s | 45 | Ꮝ | s |

| n | 30 | Ꮎ | na |

| l | 02 | Ꭲ | i |

| t | 52 | Ꮤ | ta |

| d | 55 | Ꮧ | di |

| y | 80 | Ᏸ | ye |

| k | 06 | Ꭶ | ga |

| g | 06 | Ꭶ | ga |

Computer and smartphone usage

For years, many people wrote transliterated Cherokee on the internet or used poorly compatible fonts to type out the syllabary. However, since the fairly recent addition of the Cherokee syllables to Unicode, the Cherokee language is experiencing a renaissance in its use on the Internet. For example, the entire New Testament[16] is online in Cherokee Syllabary, and there is a Cherokee language Wikipedia featuring over 200 articles.[17] Since 2002, all Apple computers come with a Cherokee font installed.[18]

Cherokee Nation members Joseph L. Erb and Roy Boney, Jr. developed an iPhone application for Cherokee language text messaging and are in the process of developing Cherokee language social network and video games.[19]

Cherokee language in popular culture

The theme song "I Will Find You" from the 1992 film The Last of the Mohicans by the band Clannad features Máire Brennan singing in Cherokee as well as Mohican.[20] Cherokee rapper Litefoot incorporates Cherokee into songs, as do Rita Coolidge's band Walela and the intertribal drum group, Feather River Singers.[21]

See also

- Cherokee (people)

- Cherokee syllabary

- Iroquoian languages

- Native American Languages

- Syllabary

Notes

- ↑ Lewis, M. Paul (2009). "Cherokee: Language of United States". Ethnologue (on-line). Ethnologue: Languages of the World (sixteenth edition). http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=chr. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ↑ Feeling, "Dictionary," p. viii

- ↑ Mooney, James. King, Duane (ed.). Myths of the Cherokee. Barnes & Noble. New York. 1888 (2007).

- ↑ Scancarelli, "Native Languages" p. 351

- ↑ Anderton, Alice, PhD. Status of Indian Languages in Oklahoma. Intertribal Wordpath Society. 2009 (retrieved 12 March 2009)

- ↑ Feeling, "Dictionary," p. ix

- ↑ Feeling et al, "Verb" p. 16

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Robinson, "Conjugation" p. 60

- ↑ Feeling, "Dictionary" xiii

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Feeling, "Dictionary" p. 353

- ↑ Feeling, "Dictionary" p. 354

- ↑ Feeling, "Dictionary" xvii

- ↑ Feeling et al, "Verb" pp. 1-2

- ↑ Holmes and Sharp, p. vi

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Holmes and Sharp, p. vii

- ↑ Cherokee New Testament Online. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- ↑ ᎤᎵᎮᎵᏍᏗ. Cherokee Wikipedia. Retrieved 12 March 2009.

- ↑ Dreadfulwater, LeeAnn. "Apple computers with Cherokee font." Pictographs: Preserving Native languages and cultures through words and pictures. 12 Oct 2009 (retrieved 5 Nov 2009)

- ↑ Proposal for the creation of RezWorld™ 3D video game to teach Cherokee. (retrieved 5 Nov 2009)

- ↑ I Will Find You song lyrics. Songlyrics.com. (retrieved 12 March 2009)

- ↑ Feather River Singers. CD Baby. (retrieved 12 March 2009)

References

- Feeling, Durbin. Cherokee-English Dictionary: Tsalagi-Yonega Didehlogwasdohdi. Tahlequah, Oklahoma: Cherokee Nation, 1975.

- Feeling, Durbin, Craig Kopris, Jordan Lachler, and Charles van Tuyl. A Handbook of the Cherokee Verb: A Preliminary Study. Tahlequah, Oklahoma: Cherokee Heritage Center, 2003. ISBN 0-9742818-0-8.

- Holmes, Ruth Bradley, and Betty Sharp Smith. Beginning Cherokee: Talisgo Galiquogi Dideliquasdodi Tsalagi Digohweli. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976.

- Robinson, Prentice. Conjugation Made Easy: Cherokee Verb Study. Tulsa, Oklahoma: Cherokee Language and Culture, 2004. ISBN 1-882182-34-0.

- Scancarelli, Janine (2005). "Cherokee". in Janine Scancarelli and Heather K. Hardy (eds.). Native Languages of the Southeastern United States. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press in cooperation with the American Indian Studies Research Institute, Indiana University, Bloomington. pp. 351–384. OCLC 56834622.

Further reading

- Bruchac, Joseph. Aniyunwiya/Real Human Beings: An Anthology of Contemporary Cherokee Prose. Greenfield Center, N.Y.: Greenfield Review Press, 1995. ISBN 0912678925

- Cook, William Hinton (1979). A Grammar of North Carolina Cherokee. Ph.D. diss., Yale University. OCLC 7562394.

- King, Duane H. (1975). A Grammar and Dictionary of the Cherokee Language. Ph.D. diss., University of Georgia. OCLC 6203735.

- Lounsbury, Floyd G. (1978). "Iroquoian Languages". in Bruce G. Trigger (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 15: Northeast. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 334–343. OCLC 12682465.

- Munro, Pamela (ed.) (1996). Cherokee Papers from UCLA. UCLA Occasional Papers in Linguistics, no. 16. OCLC 36854333.

- Pulte, William, and Durbin Feeling. 2001. "Cherokee". In: Garry, Jane, and Carl Rubino (eds.) Facts About the World's Languages: An Encyclopedia of the World's Major Languages: Past and Present. New York: H. W. Wilson. (Viewed at the Rosetta Project)

- Scancarelli, Janine (1987). Grammatical Relations and Verb Agreement in Cherokee. Ph.D. diss., University of California, Los Angeles. OCLC 40812890.

- Scancarelli, Janine. "Cherokee Writing." The World's Writing Systems. 1998: Section 53. (Viewed at the Rosetta Project)

External links

- Cherokee Nation Dikaneisdi (Lexicon)

- Cherokee (Tsalagi) Lexicon

- Echota Tsalagi Language Project

- Cherokee New Testament Online Online translation of the New Testament. Currently the largest Cherokee document on the internet.

- Exploration of the Red River of Louisiana, in the year 1852 / by Randolph B. Marcy ; assisted by George B. McClellan. hosted by the Portal to Texas History. See Appendix H, which compares the English, Comanche, and Wichita languages.

- Unicode Chart

- Official Cherokee Font (Not Unicode-compatible)

- WikiLang Cherokee page (Basic grammar information)

- UNILANG forum for freely available teaching materials. (Includes PDF textbook and audio files).

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||